Excess of red

The photograph as a family collectible has become a thing of the past. Today, old vernacular photography has immense documentary value. Yet Soviet household

photography, such as found family albums, with its recognizably stiff poses and a well-defined range of themes, is in fact a means to conceal the real state of affairs. Private photography was

not private at all. Control mechanisms were applied not only to official or newspaper photography, but deeply penetrated into the realm of household photography as well. A photo album could be

used as evidence against those portrayed in it. Hence it had to be ideologically flawless: rather than a reflection of reality, it was a testimony to oneʼs full compliance with the stereotype of

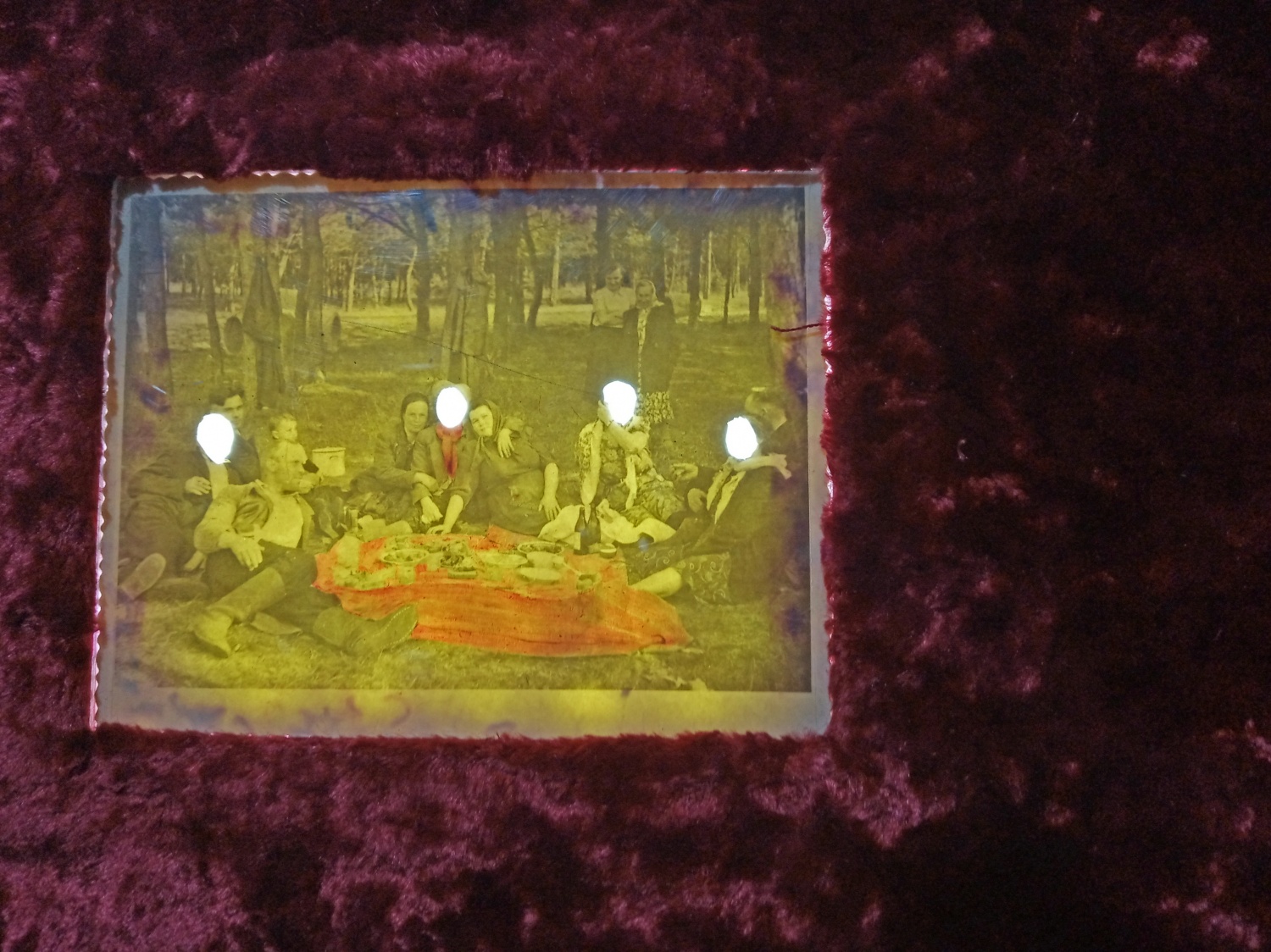

the model Soviet citizen. One of the most popular themes in the Soviet photo albums is the family feast, which was, perhaps, supposed to demonstrate serenity and security of life in that country.

Only by accident would reality leak out – when suddenly one or several faces in the festive photo were painted over or cut out. The presence in your picture of someone undesirable, repressed, or

liquidated could make you disappear too. All of this could be termed “visualization of concealment”, both as a photographic genre and a way of life.

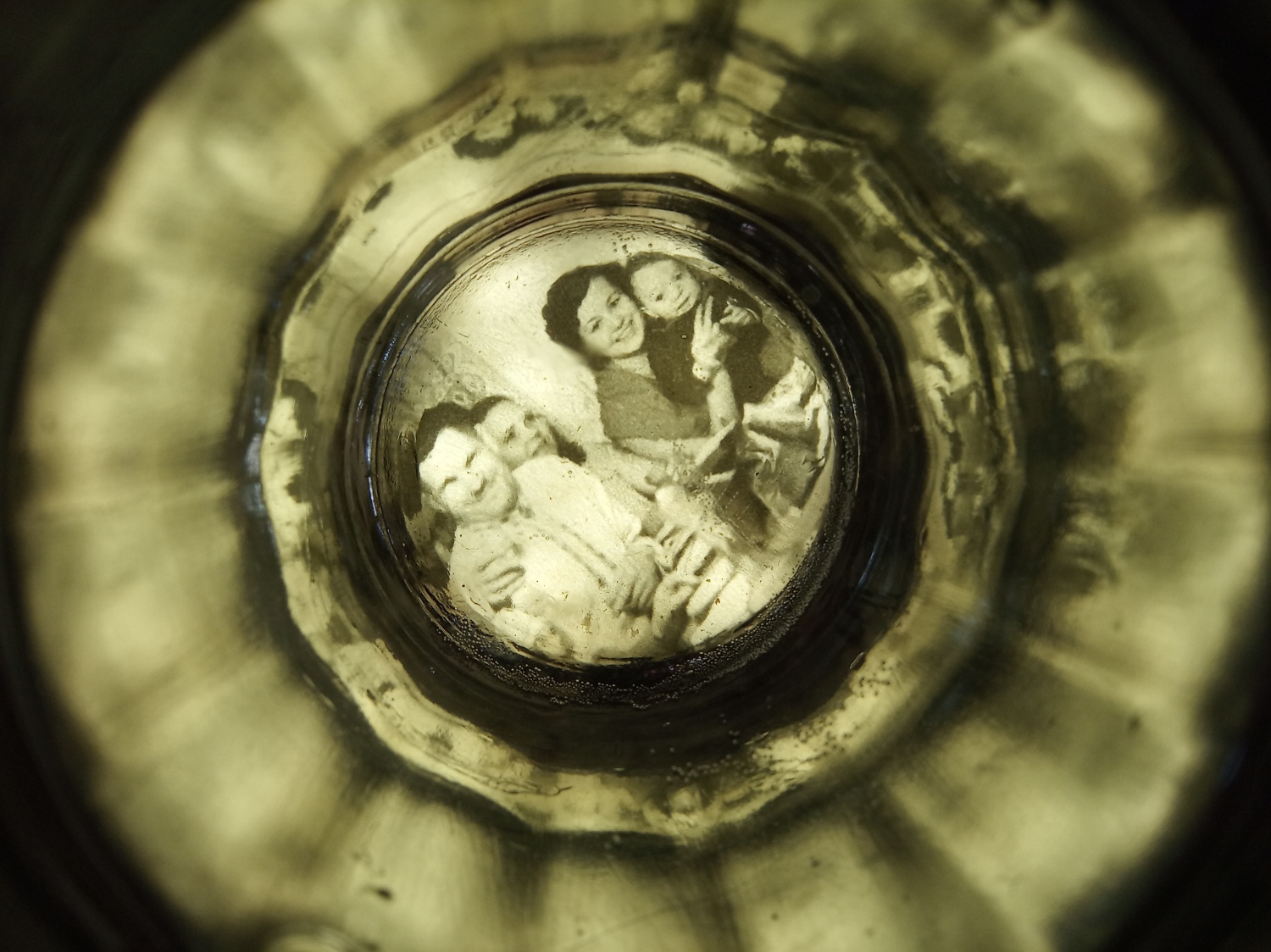

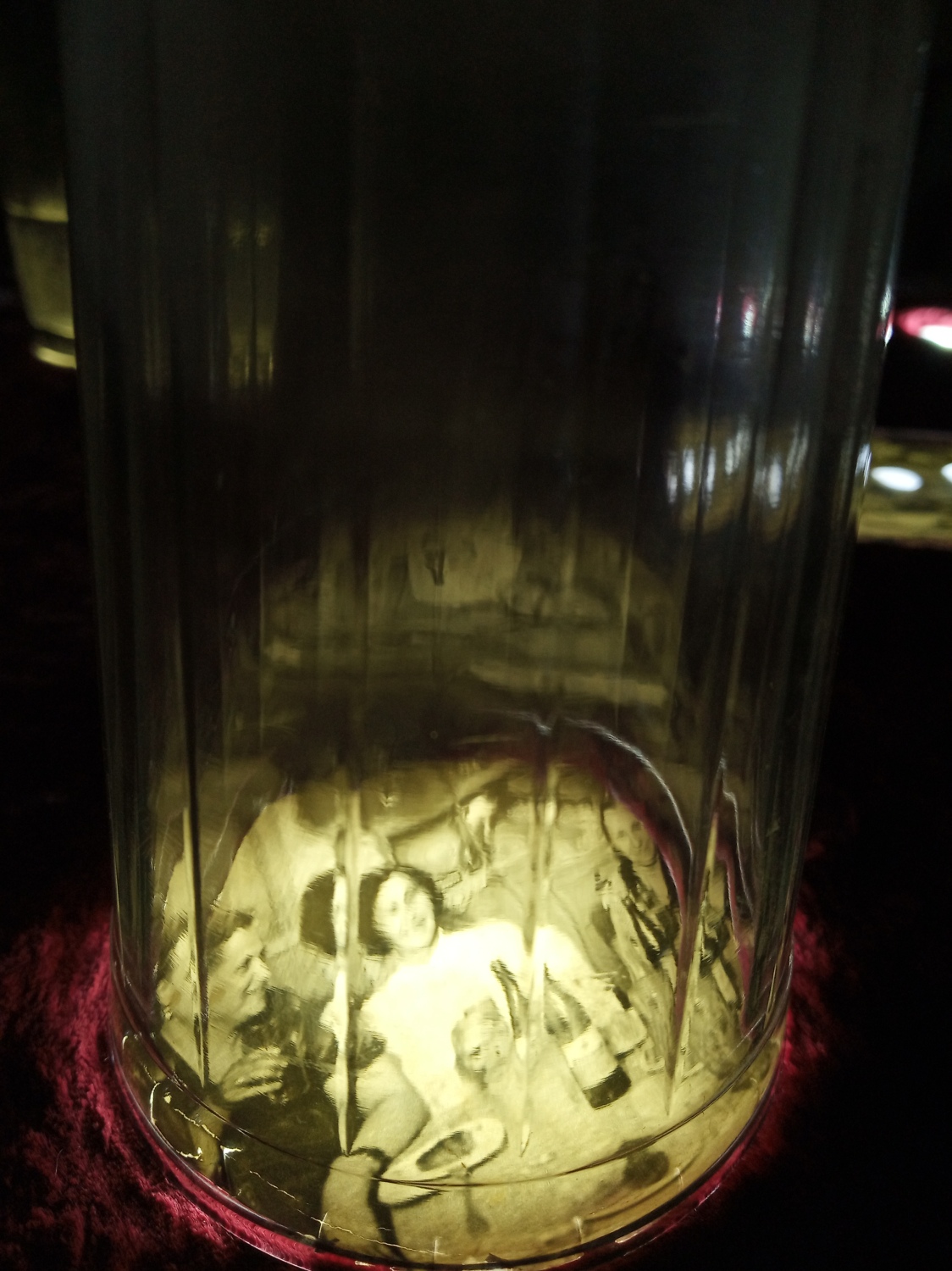

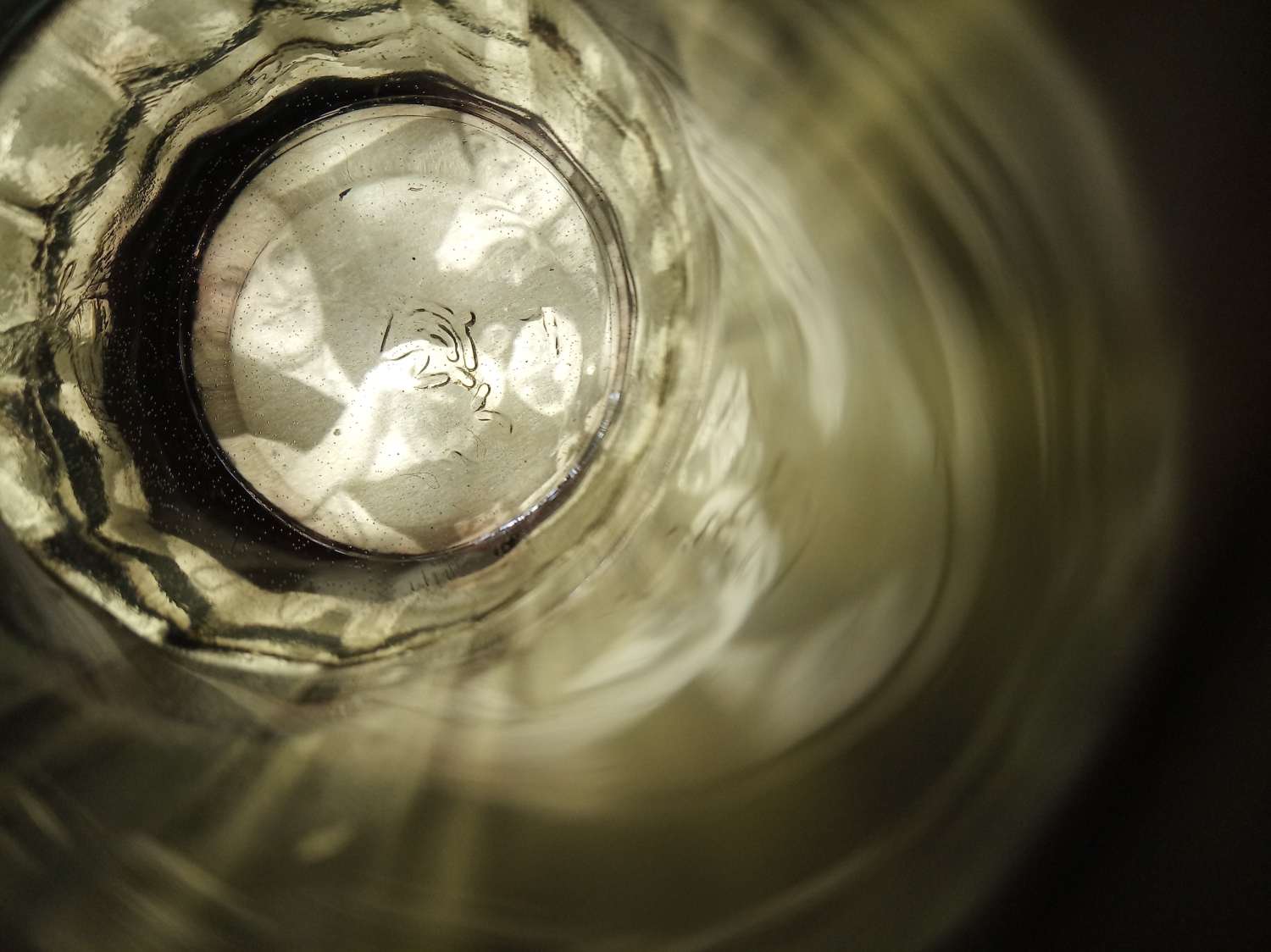

The festive table presents us with is an interesting “multifaceted” metaphor – the typical Soviet faceted glass, also an instrument of deceit, which, thanks to the

refraction of light, conceals the amount of liquid poured into it. At the same time, when turned upside down, it signals the end of the feast.

Faceted (cut-glass) ware is strong. Such glasses are almost unbreakable. But the culture of refraction and distortion, as if embodied in that typically Soviet glass,

is just as durable. The faceted glass still preserves a phantom of the past, on which we now blame our present, avoiding responsibility and a clear-eyed look at our own history.